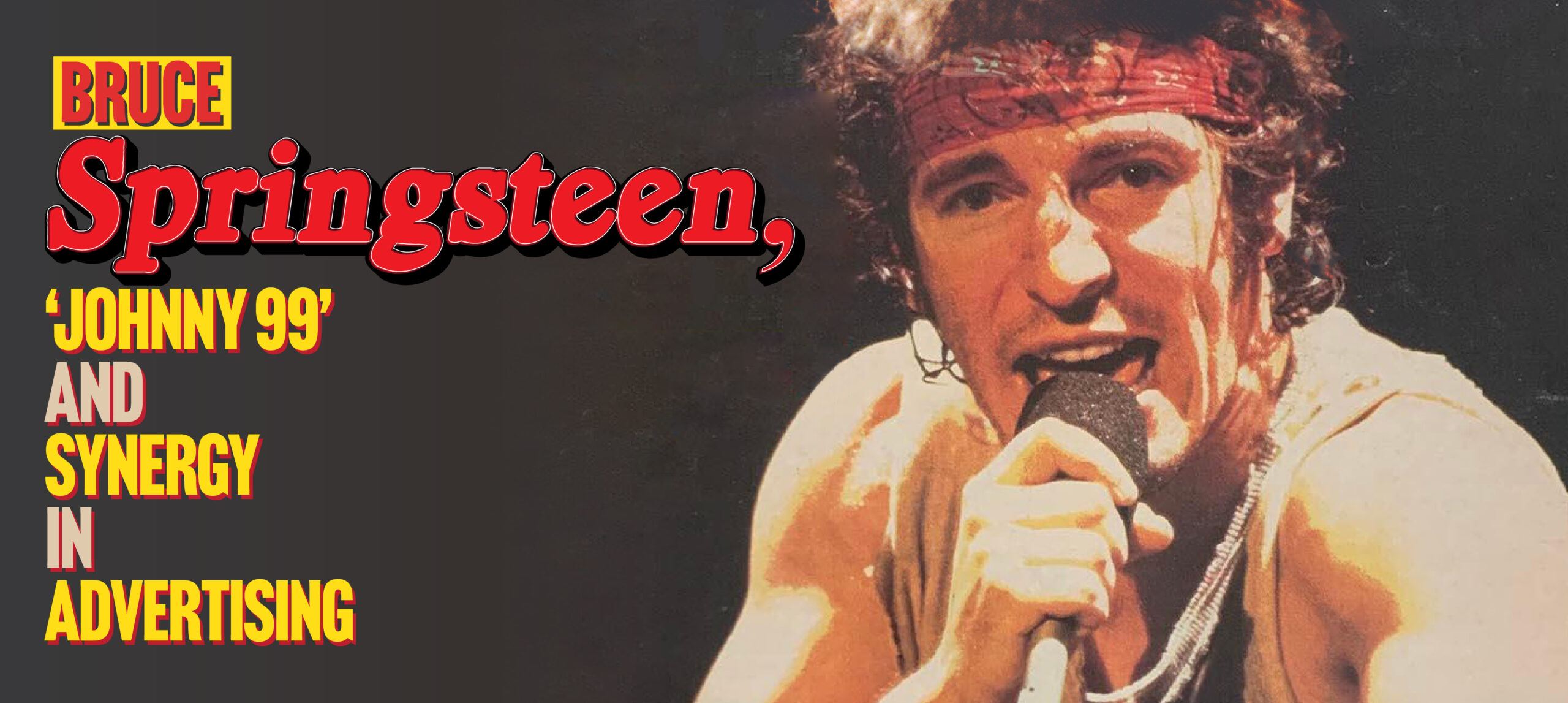

Bruce Springsteen, for those who may not know, is an American singer-songwriter-performer. Bruce Springsteen, for those who may not know me well, is one of my heroes and, once I get started, I don’t stop talking about him. Over the years, ever since I discovered his music, I have learnt a lot from his lyrics, as well as from the way he conducts himself – both professionally as well as personally. Unexpectedly, though, I also learned a lot that helped me in my advertising career. From how he has figured out a brand purpose for his music (“To measure the distance between the American dream and American reality”), for his mighty E Street Band (comradeship, loyalty and as much part of the audience as the audience itself) and his performances (part tent-revival, part party, part mirror to society) to how he tries to stay true to all of the above. Thankfully for you though, Dear Reader, this article has a word limit. So, I’ll stick with what I learnt about advertising from ‘Johnny 99’.

‘Johnny 99’ is a short story-song about a man named Ralph off Springsteen’s 1982 acoustic solo album, “Nebraska”. Ralph is a factory worker who gets laid off and is on the verge of losing his mortgaged house to the bank. Distraught, he gets utterly drunk and, out of control, ends up shooting a night clerk. A judge consequently sentences him to 99 years in prison, but Ralph begs, instead, to be executed.

On the album, the singing is almost deadpan, reflecting Ralph’s bleak situation. The only accompaniment is a jaunty acoustic guitar that rushes him to his fate, interspersed by a breathless harmonica that heightens the effect. The whirlwind of a life Ralph has no control over.

When Springsteen performs it live during his 1984 tour, the interpretation remains very close to the original, except the singing lingers precariously somewhere between despair and defiance.

However, in later tours, the performances change dramatically.

In 2005, for example, during an intimate solo concert, the acoustic guitar changed to an electric one, which slashed through every syllable, while Springsteen shouted out the lyrics. This he did through a ‘bullet mic’, which distorted Springsteen’s voice to make it sound like he was using a decrepit police loudspeaker. The song would suddenly end mid-shout, leaving in its wake a sudden vacuum of silence – as if it itself had been executed. The ‘bullet mic’ made it difficult to hear the words (cannily forcing the audience to listen harder), but you could most definitely feel the rage – and its abrupt silencing. As it often happens with the economically disadvantaged, whose voices are rarely heard, but easily silenced.

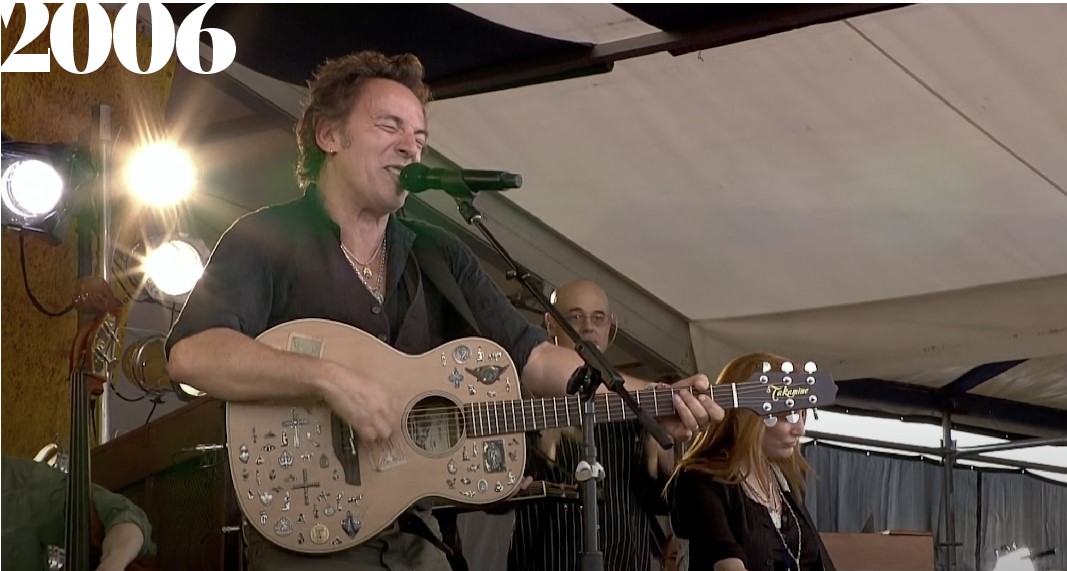

The following year, Springsteen performed at the New Orleans Jazz Festival to help restore the spirits of a community left devastated by Hurricane Katrina. ‘Johnny 99’ was recast yet again; this time, even more dramatically. An 18-member band accompanied him, with instruments so diverse that they included a banjo, a washboard, an upright bass and an entire horn section, which included even a tuba. That one song itself also contained within this interpretation a potpourrie of genres, including, but not limited to, zydeco, gospel, blues, bluegrass, honky-tonk and swing.

It was the triumph of the underdog…or, at least, of the longevity of his tale. The story of the human condition, the prisons of circumstance and of the mind, were in the lyrics and in the full-throated, pained singing, but the possibility that some chains could be broken was in the music. You could almost dare to dance to it.

During Springsteen’s 2014 tour, however, you actually could dance to it. ‘Johnny 99’ was now pure, unadulterated rock n’ roll – guitars, bass and drums and a backbeat groove your feet couldn’t ignore. He was performing to stadiums around the world and it got the crowd jumping – like so many ‘social-commentary’ songs in ’50s and ’60s Americana that were often set to infectious tunes so that they would stick to a listener’s subconscious. These were stories that needed to be heard and, therefore, needed to grab every ear in order to spread – and persist.

I suppose you’re possibly now thinking, “That’s all very well, but what has any of the above got to do with advertising?”

Several years ago, when digital media was just about taking off, I was attending one of the annual 3-day GoaFest advertising awards events. There, I happened upon a discussion on synergy, with respect to advertising and communication. Most of the distinguished speakers spoke about how colours and design and tone of voice created synergy – you recognised brands by these very things. Yet, this didn’t feel particularly enlightening to me, personally. It was something that had already been ingrained in me since when I was an intern.

Just as my attention, I have to confess, was beginning to drift, a new speaker came to the microphone. Unfortunately, I can’t recall today who he was, but what he spoke about drew my attention back to the seminar. Something that I have not forgotten ever since.

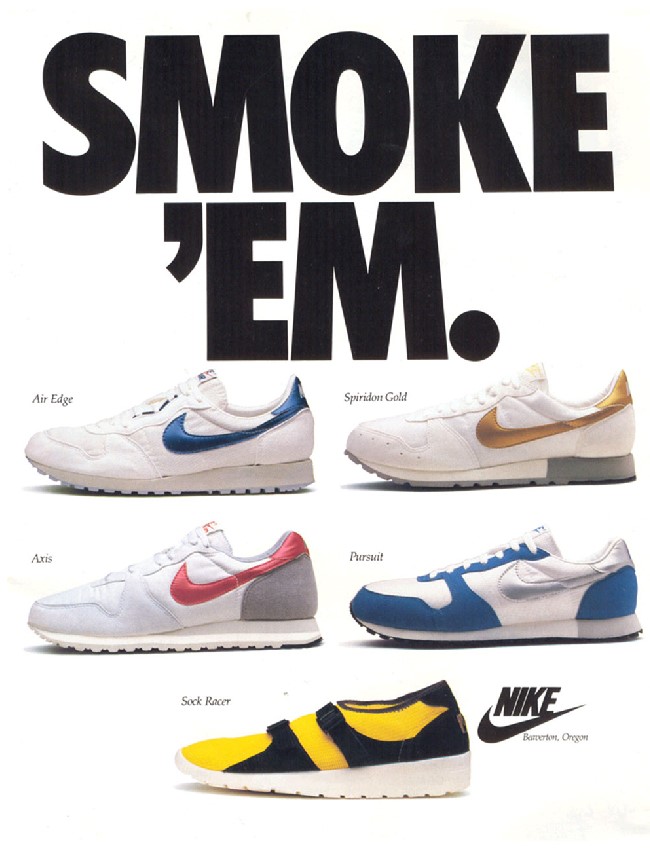

He said that you needed only two things to establish and maintain synergy: the message and the logo. The rest was vanity and counter-productive. Once the dust – and the murmurs – settled, he explained further. He suggested that everything else that we standardise and templatise often serves only to create blind spots. According to him, the target audience may get so used to the pattern and the format that they may not feel engaged enough to actually pay attention to the actual content – one can miss the trees for the woods. Moreover, this was equivalent to spoon-feeding; but, if you spoon-feed, the audience doesn’t need to pay attention to the food. To demonstrate, he displayed several Nike ads. Each had a different tone, a different look, a different style and, on occasion, even different interpretations of the logo itself. During the presentations prior to his, several presenters had showcased their own selection of ads. I realised then that this was also one of the reasons I was beginning to get bored during the earlier presentations – it had felt like they were showing us the same ad over and over again. Each Nike ad, on the other hand, had seemed to trigger a different part of my mind. Each ad felt fresh and made me curious to discover what it was about. Granted, Nike is a brand that not only challenges limitations, but defies them as well; still, the presentation gave me – and, certainly, many others – lots to think about.

Afterwards, I started noticing this whenever it happened. Whenever it did happen, it thrilled me no end. In fact, there’s one industry where this happens very, very often and I’m pretty sure you would have noticed it too, Dear Reader. It’s done so nonchalantly, it’s almost mainstream; so frequent a practice, it ought to have demonstrated to many brand custodians – on both sides of the aisle – how little the risk is, in doing so. That industry is cinema. Most (mainstream) international movies begin with a big reveal of the production house logo and, so very often, they reimagine it to suit the theme of the movie. Yet, it never diminishes the power of the logo and, on the contrary, enhances the overall experience. It’s disruptive, not destructive. In fact, I must admit that now, when I begin watching a movie, I look forward to seeing how the logo will be interpreted for that movie – and I almost feel a pang of disappointment when they don’t attempt to.

Then, of course, there’s digital media. Today, many brands do speak with multiple voices and languages. They speak in the voice of their ‘digital audience’ and in the language of whichever site the user might be on. Identifying and capturing this difference in voice and language, I recall, used to be something that led to the bookings of many office boardrooms when digital media was truly taking off. Which should have made this entire article redundant.

Sadly, this article still remains relevant. I’ll first quickly touch upon why and then also attempt to further the conversation in order to anticipate the future of synergy in brand communication.

Many brands hold on to their precious identity with tentacles so strong that they often appear very out of place in the digital realm. They somehow still refuse to adapt. Often, these same brands don’t seem to have a large following, either. If you are not seen, you don’t exist. Philosophical as it may sound, it’s true at a certain level. Maybe these brands should consider changing their attire.

Furthermore, this seemingly provocative approach to synergy, in my opinion, should be adopted in the mainline space as well.

Do all Red Letter Day (Mother’s Day, New Year’s Day etc) communication, for example, have to sound either like a corporate memo or a Hallmark card? How about funny, instead? Or anti-authoritarian? Or street smart? Or, practical and honest? Why can’t a serious brand smile, too? Why can’t a brand be both authoritative and inviting? Or childish, yet wise? And so on.

Why can’t a brand take off its uniform every once in a while?

I think it’s because we, client and agency, often confuse the word ‘parameter’ with ‘restriction’.

In today’s day and age, people are responding more and more to the humanity in a brand and, like humans, I believe that brands should be all the things that humans are – funny, serious, gentle, provocative, mischievous, silly, sombre, enraged etc, depending on what is being said, to whom and where. Brands cannot afford to wear single set-in-stone faces if they hope to remain relevant, engaged and engaging.

I do understand the concern over losing one’s identity, of course. I am not suggesting we discard parameters, but that we reinvent them – by drawing from humans.

Think of two or three or how many ever different people you might know. You will have no trouble differentiating between their personalities. Yet, I’m sure they each would be funny, serious, gentle, provocative, mischievous, silly, sombre, enraged etc in their own unique and distinct ways. You would not confuse one with another, or even confuse one’s particular trait with the same trait in another. Ditto with brands, is my submission.

There is no one single thumb rule in advertising when it comes to synergy (or many other things, for that matter). However, I do believe that this is something worth pondering upon and considering seriously.

Which brings me back, as I end, to ‘Johnny 99’ (aren’t you glad this had a word limit?).

When jazz fans in New Orleans needed hope to rise from ruin, this song did the job. When a stadium full of rock n’ roll fans wanted to dance, this same song did that job. When a lone man wanted to howl in pain in 2005, to an audience which preferred acoustic music, this song did the job. If one really thinks about it, indeed, this song’s true job was to reach as many – different kinds of – people as it could, no matter where it found them. To do so, it had to ensure it remained contemporary, immediate, interesting, relevant. It had to adapt, allowing its various aspects and facets to constantly create both intrigue and familiarity in order to keep making new friends.

Synergy was maintained by only two factors.

The message: the lyrics.

The logo: Bruce Springsteen.