‘Under every good ad, there is always a good key number’ that’s the Rediffusion corporate ad I wrote for a souvenir. Key numbers are, I am told, obsolete, and so are the days when ‘Advertising used to be the most fun you could have with your clothes on’ (not mine, but Jerry Della Femina’s, a copywriter who wrote the bestseller, ‘Those Wonderful Folks Who Gave Us The Pearl Harbour’, a novel set in an advertising agency where the title line was the headline for an ad for launching a Japanese brand of TV in America!)

In 1976, I was Associate Creative Director at Grant Advertising, billing wise probably the 5th largest agency in India and, one fine day, I saw an ad done by a small, unheard of agency called Rediffusion. It was an ad for Bush Calculators and showed calculators as scientists, engineers, doctors, professors! ‘My God,’ I said to myself, ‘this is the kind of work I should be doing!’. So I called Rediffusion, got the address and walked into their office, which had its entire staff of 10-11 people, including the bosses Arun Nanda and Ajit Balkrishnan, in that small 4th floor room at Readymoney Terrace, reputed to be a haunted building (hence Rediffusion could afford it, I guess). Arun and Ajit did not much care for my portfolio and gave me, the Associate Creative Director of India’s 5th largest agency, a copy test! I admired their guts and met Arun Kale, their Art Director. Kale was my senior from Sir J. J. Institute of Applied Arts days, so we shared gossip about our common friends for 30 minutes and, in the remaining 15 minutes, produced 6 campaigns and showed it to Arun across the glass partition that divided our room with his.

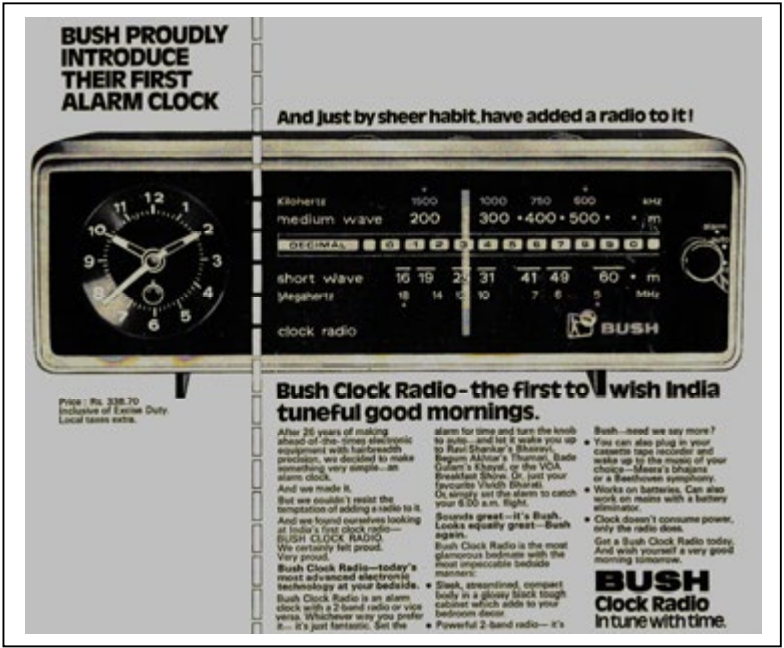

He liked all of them but sold ‘Bush Clock Radio proudly announces their first alarm clock. And by sheer habit, they have added a radio to it’ to the client. ‘But we can’t afford you,’ said Ajit Balkrishnan. I was 29, I was single, I had no expensive habits, no girlfriends either. I said, ‘So what?’. So, Ajit took me for a corporate lunch to the Udipi restaurant downstairs.

That’s how I became perhaps the first adman in the history of Indian advertising who changed his job for a lower salary (not unusual, because in 1970, I had already become the first English copywriter in Indian advertising who came from the back waters of Ballia, spoke and wrote grammatically incorrect English and had applied at Hindustan Thompson, India’s number one advertising agency, because I needed a job to have a haircut. And had got it!).

As if offering me a lower salary was not enough, they asked me to cancel my holiday because they had been invited to pitch for Red Eveready, competing against the top four agencies. I lied to my parents that I have changed my job for a better salary but have to stay back to work on a very important pitch.

After I joined, they asked me what designation I would like on my visiting card. Since I was the only copywriter and, unlike the present generation of creative people, I was never in the race for chasing visiting cards, I said I would be quite happy with ‘Copy Overseer’, ‘Copy Superintendent’, ‘Copy Dealer’…anything. Since I was the only copywriter, I was virtually the ‘Copy Department’. So, when I went to the loo, the Rediffusion Copy Department was located in the loo.

Arun Nanda took 6 campaigns done by me and Kale to pitch for Red Eveready and, for the first time in the history of Indian advertising, unsold our own campaigns one by one till the client got fed up and surrendered to Arun Nanda and begged, ‘Please, tell us which one should we buy?’ The campaign Arun finally sold was ‘The Chosen One. For your Transistor’. No, the story does not end here. Ajit and Subhash Chakravarty (our Calcutta Office Head) wanted advance payment from the client without which Rediffusion was not ready to accept their account! And they got it.

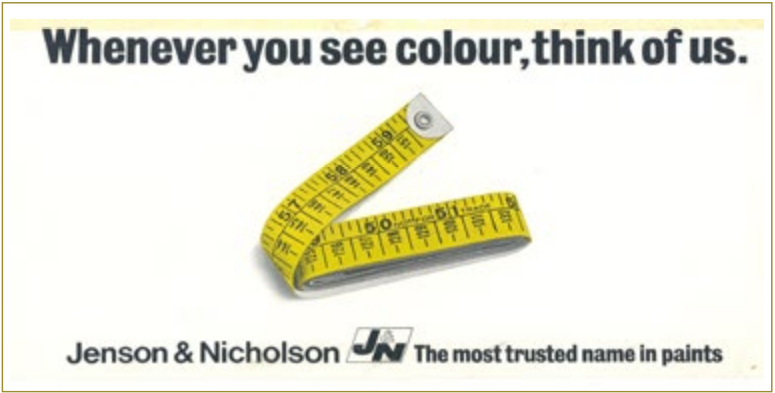

Our Calcutta office didn’t have a phone, so Subhash Chakravarty used to call us from the grocery store next door. Rediffusion had already made history with their print campaign for Robbialac Plastic Emulsion wall paints by inviting consumers to real homes painted with Robbialiac Plastic Emulsion and check for themselves the washability, durability and the range of colours. They wanted an outdoor campaign. The grocery store had fixed the number of times Subhash could use their phone, so he was running out of excuses to the client for postponing deadlines. Kale and I were overworked because all creative for all branches were centralized at Mumbai Head office. So, one fine day, Kale and I were taking a leak in the toilet and wondering what to do. I said, “Kale Saab, I am solving my problem once and for all by creating a line, ‘Whenever you see colour, think of us’. And since everything in life is colourful, your job too is solved once and for all because you can virtually put anything as a visual with my line.” The first visual was a fried egg; the rest is history. That outdoor campaign ran for over 15 years because you virtually cannot run out of colour in life around you. And you never know where and from what a major campaign is going to leak out.

Television was a hot new medium, but advertising agencies were simply editing their 1-minute cinema commercials into 30 seconds and releasing them as TV ads. It may be that my skill as screenwriter was honed during this period when I literally invented the sitcom format for TV commercials. I created a series of 20-second TV commercials, using Dalip Tahil playing different characters, which sold Robbialac Plastic Emulsion through humour and entertainment. This is because I have always believed that the real competition for an ad are not other ads but the medium itself. So, in a newspaper, your print ad is not competing with other print ads, but with the news. And, hence, it better be more interesting than the news. Similarly, on television, which is primarily a medium for entertainment, your ad is not competing with other TV ads but with the entertainment on TV. One of the commercials showed Dalip Tahil as ‘President Bundalanno of the People’s Republic of Marijuano’, telling his people, ‘What this country needs is neither democracy nor dictatorship, it needs durability. The paint on walls of this country lasted longer than the last regime – it was Robbialac Plastic Emulsion Paint!’ This was my subtle way of commenting on Indira Gandhi’s Emergency (it was 1976). Sure enough, the censor board at Doordarshan took objection to the commercial. But not because I had referred to democracy and dictatorship, but because the Indian Government would not like to spoil its relationship with ‘President Bundalanno of the People’s Republic of Marijuano’! It was not easy to convince Doordarshan that ‘President Bundalano of the People’s Republic of Marijuano’ was not a real president of a real country. The same problem happened when I used Thomas Alva Edison (played by Harish Bhimani) for an HMT Bulbs TV commercial. The Doordarshan censor board expected me to get an ‘NOC’ from ‘Thomas Alva Edison’ himself. They were very upset when they were told that it would be rather difficult because he has been dead for more than 40 years! With Doordarshan censorship being what it was, we always found ways to get away with what we wanted to show on TV. For example, Colgate was launching a new premium soap called Palmolive. As usual, I was so overworked, I had no time to prepare for the client meeting. It was lunch time when I met Wolfgang, the Marketing Head of Colgate-Palmolive. My pitch was very simple (and deviously erotic) — ‘Imagine a bar of Palmolive soap melting on the bare skin of a beautiful naked woman like a blob of butter melting on hot toast!’ Wolfgang was actually having hot toast with butter melting on it. ‘When can I see it, Kamlesh?’ is all he said. So, I got hold of the cameraman, Late Ashok Mehta who had recently shot Rekha beautifully in ‘Utsav’ and shot the commercial. Wolfgang bought it but I knew Doordarshan would never let it air. So I first created a storyboard, which showed a lot more skin than we had shown in the film. Doordarshan promptly put their foot down. How could we show so much nudity? Our argument was deviously simple — what if we showed much less? At the meeting, the Doordarshan folks compared the storyboard with the film and expectedly found the film far more acceptable than the storyboard!

Sandoz Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals were very good clients, besides being almost our neighbours at Worli. They were very good paymasters and our salaries mostly came from them and so, I always tried to keep them happy. One of my favourite lines that I wrote for them was ‘The fastest colours that never run’. We were always overworked and understaffed. Sometimes, I would not have an account executive to take the artwork to Sandoz for their approval. We had a peon John. He used to drink. So I promised him an ‘Addha’ if he could take the artwork to Sandoz and would not move till the Sandoz executive approved the artwork with his signature. And John had a 100% hit rate in getting my creative approved! You can’t imagine what half a bottle of booze can do!

New Delhi’ was fun to write. M. J. Akbar was going to bring out a classy and the most expensive magazine for men in India (Rs.5/-per copy!) on the lines of the American Esquire magazine. When I asked what kind of features it would carry, he just dropped a line ‘The curious poverty of highly paid executives in India’. I got the drift. I followed it with ‘How young did your God die?’, ‘Do mistresses make major corporate decisions?’ and so on. Kale excelled himself in visuals and I enjoyed writing long copy for those ads because they were expected to mirror the articles the magazine would ultimately carry. The campaign won many awards, but the magazine failed because it could not live up to the expectations built by its advertising. M. J. Akbar (BJP MP now) and I still laugh about it.

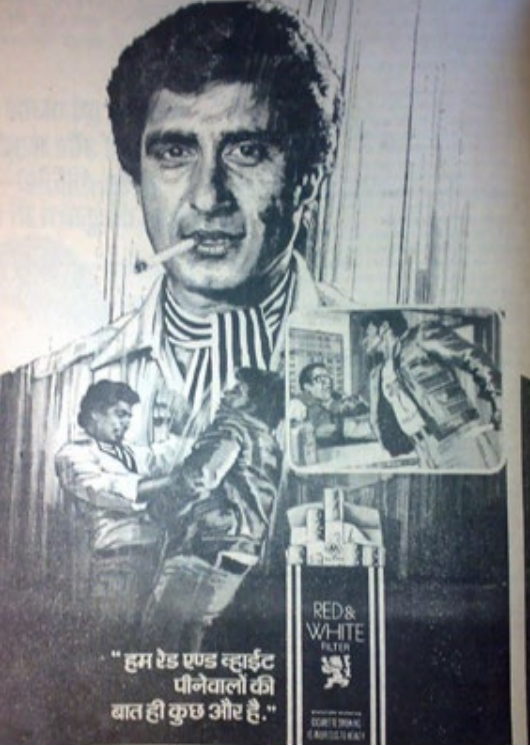

Cigarette advertising those days was limited to selling taste, flavour, made for each other or living life king size. Red & White cigarettes were a cheap brand, which could not claim any of those attributes. I was, perhaps, one of the first copywriters who had brought the sensibilities and archetypes of mainstream Hindi cinema into advertising.

At HTA, as a trainee copywriter, my script for Bombay Dyeing had saved the account for the agency because Nusli Wadia had rejected 49 campaigns earlier. The film, shot by Zafar Hai, was simple – three goons enter the Bombay Dyeing basement to rob their safe. They ignite the dynamite and then discover the goodies and begin to try them out while the dynamite wire burns. The safe explodes and there is just a small placard saying ‘Steal the Show in Bombay Dyeing’. My then creative director at HTA, Andre Syson, gifted me the first screenplay I ever owned — the screenplay of ‘Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid’ by William Goldman. It was Andre who had prophesied that someday I would write movies (when Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra was casting ‘Rang de Basanti’ in London, his model coordinator took my script home. Her father saw my name on the script and jumped with —’I know this guy!’). Now back to Red & White cigarettes. I wanted an ordinary, humble, unheroic guy who does something heroic but, instead of being recognised as a hero, prefers a few puffs from his Red & White cigarette as reward enough, saying ‘Hum Red & White Peenewalon ki baat hi kuchh aur hai’. For casting the ordinary, humble, unheroic man, I asked my friend Late Ravi Chopra to send three options. He sent Mahesh Anand, who used to play the henchmen of mainstream villains; Mazhar Khan, who was considered to be the next Amjad Khan after his performance in ‘Shaan’, and Raj Babbar, who was a nobody, still shooting for ‘Insaf Ka Tarazu’. I chose Raj Babbar. And the brand became so successful that, after the release of ‘Insaf Ka Tarazu’, wherever Raj Babbar went, the audience bombarded him with empty packs of Red & White cigarettes, shouting my line.

I stole from mainstream Indian cinema again for a commercial for Garden saris. In Kamal Amrohvi’s ‘Mahal’, Madhubala, the mysterious leading lady, was singing the haunting song ‘Aayega…aayega…aayega…aayega aanewala…’ on a swing. I took the swing, sat Arti Gupta on it and, as the swing moved to Vanraj Bhatia’s music, the Garden saris on Arti Gupta kept changing with every swing!

We were always running from one deadline to the next. Colgate was launching a new toothpaste – ‘Colgate Fluorigard’ – aimed at kids. And, as usual, I had nothing to carry to the client for the meeting. I panicked. Panic, in my view, is the most productive tool for creative people because thinking stops and what comes out is so totally unusual, it surprises even the creator. I asked my Art Director and ex-professor Avinash Godbole to just draw some kids waiting in a valley in an early misty morning. And he did, in about 10 minutes. I rushed to the client meeting. I had nothing to show, no storyboard, no script, no line, nothing. So I took a leaf from ‘Space Odyssey 2001’ and, just like what I had done for Palmolive soap to Wolfgang, I started telling him a story — ‘Imagine a valley early in a misty morning. There is a crowd of expectant kids waiting for something. Suddenly they see a monolith in the sky. It slowly begins to descend. It lands on the top of a mountain. It is a huge pack of Colgate Fluorigard. The kids begin to shout the brand name and the super says, ‘On August 15, 1981, the kids of India will get freedom from cavity’. Director Pankaj Parashar had a tough time on the set at Famous Studio controlling 300 kids who all wanted to go to the loo at the same time.

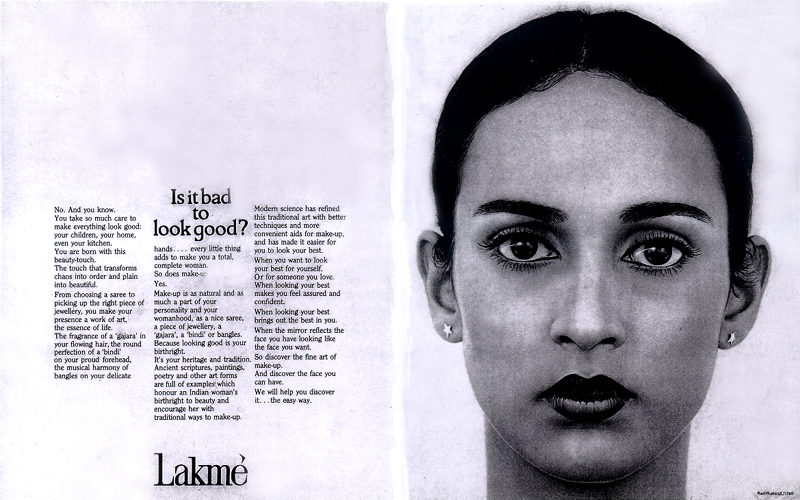

Lakme had always advertised on the back pages of magazines with beautiful colour ads showing a well-dressed model and the range of lipsticks and nail enamel. So when we went with our black and white campaign to Mrs. Simone Tata, our client, she blew her top. Our research had shown that most middle-class Indian women considered make-up wrong because it meant they were, trying to attract men. We wanted to break the taboo and extend the market for Lakme to middle-class women in small towns. So we did a taboo-breaking theme, ‘Is it bad to look good?’ Mrs. Simone Tata was so upset, she told our Bombay Branch Manager, Vishwanathan, who went on hard-selling her the black and white campaign, ‘Mr. Vishwanathan, I don’t want to see your face!’. But those days, we had tigers for executives. Vishwanathan replied, ‘Mrs. Tata, I don’t care if you do not like my face, but this is the campaign you are going to buy!’

Ultimately, she not only bought the campaign, the campaign won many awards and Lakme sponsored the first Cag Award for the Best Copywriter, which I went on winning consecutively for five years till I stopped entering my work. She remembered to send me a very sweet note. The commercial for Lakme was tricky – how to find something that combined lips and nails in the same frame? So I gave the model Shyamali Verma a flute to play. In the commercial, as Shyamali Verma plays the flute, the shades of her lips and nails keep changing. Hari Prasad Chaurasia played a bamboo flute but in the film, Shyamali Verma was playing a metal flute. But who would notice the discrepancy other than connoisseurs of classical Indian music?

Our clients, in fact, used to be intimidated by us. Perhaps, because we sold our work hard and we kept winning hundreds of awards for our work from Cag, Ad Club, RAPA and other advertising institutions. At award functions, it was left to our peon John to fill a sack with all the awards and carry them to the office while still punch drunk from the award party. In fact, our clients felt obliged to like and approve our work because otherwise they might be considered incapable of evaluating and appreciating good creative! And we did nothing to change their perceptions!

When colour TV in India was being launched in 1982, no manufacturer had the product ready; they were all just taking bookings. There were long lines in front of dealers of popular brands. Our client, Bush wanted a creative that didn’t cost a dime and yet got them longer lines in front of their dealers’ shops for booking their brand of colour TV. So, I gave one – we hired 100 black and yellow Mumbai taxis and paid them 100 rupees per day to carry a cardboard carton with the Bush Colour TV logo on it strapped to their roof carriers and asked them to just drive around town from dawn to dusk. That gave the consumers the impression that, while others were still taking bookings and giving a 6-month waiting period for delivery, Bush was already delivering! It was devious, but it was not unethical; Bush was indeed delivering cardboard cartons to their dealers! We couldn’t help if the consumers got the wrong impression!

These are just a few that I could remember at my ripe old age of 73!

And my words of advice to young creatives? I am not sure if they are ready or even willing to take my advice – they all seem to know everything that there is to know, anyway. Advertising has always been a passion for me, a love affair, a vacation, not work. I remember we used to be so anxious to get to the office every morning to attack a brief (sometimes, we did the creative first and asked the executives to write the brief around it. Our clients used to be so impressed because the creatives fitted the briefs perfectly!) that we would land up when the office was not yet open! It was really like a vacation! That’s why we could not only survive, but excelled in whatever we were doing in spite of being overworked and understaffed. I used to define advertising as, ‘Vigyapan mann ka itavaar hai’— Advertising is a Sunday for the mind! And if every day for you is a Sunday, what more can you ask from life?

And how has advertising changed over the years? I have been out of advertising for a long time, so I really do not know how advertising has changed. But whenever I meet some advertising people and ask them how is work, I get the feeling that it is no more ‘the most fun you could have with your clothes on!’